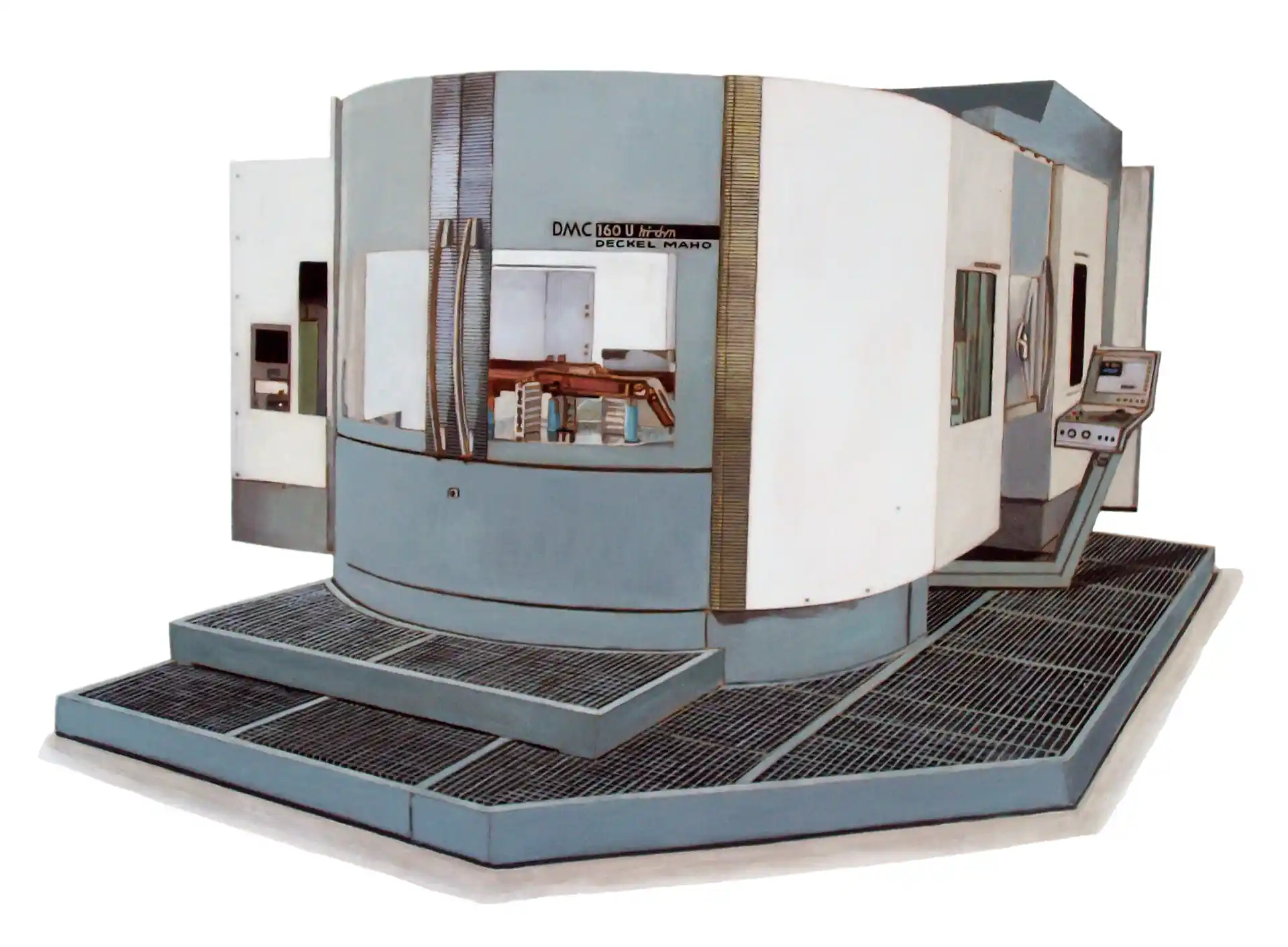

Bert Ernie stole a brochure (attached to a trade magazine) from the library at Dandenong TAFE for the sole purpose of painting this image.

It then took 481 hours to turn that brochure image into a photorealist painting.

This paintings subject is actually about accuracy of painting, verisimilitude and photorealist art. The highly accurate and programmable CNC machine is the perfect metaphor.

Dimensions: 91x123cm

Painted: 2008

Materials: Acrylic on MDF board

Private collection

The story behind Deckel Maho Gildemeister

A painting of a brochure for some kind of machine – why would I paint something so odd? This Deckel Maho Gildemeister artwork is a photorealist painting that uses the object depicted (in this case a high-tech metal cutting machine) to speak of something that will seem unrelated – but is, in fact, the best metaphor for the subject. And that subject is photorealism. More specifically, accuracy, which is a fundamental requirement for the visual trickery that all photorealistic art must employ if it is to be convincing to the viewer.

Bert Ernie has painted something that is going to be entirely unfamiliar to the average person but is worthy of their attention. This type of machine depicted here is the ultimate sculpting tool ever made by humankind. It is the machine that makes many our modern material goods possible. The car you drive, the fridge in your home, the phone in your hand – they all were made possible by this machine. This machine is known as a CNC machine – the CNC stands for Computer Numerical Control. This particular machine is a milling machine. More specifically, it is a 5-sided, 5-axis machine. Basically, that last bit means it is the most capable. Its purpose is to cut metal into any shape. And that’s why it is so important. Almost all consumer goods owe their physical appearance to this kind of machine.

Bert has known of the computer control of metal cutting machines since he was about twelve years old. He has been fascinated by them ever since. They represent power, sophistication, extreme accuracy, and an incredible amount of capability. Let us expand on each of these points first before we move on the more artful aspects. It is essential to understand where Bert is coming from.

Power. These Deckel Maho Gildemeister machines are quite powerful. They have to be to cut metal. This one has an electric motor with similar horsepower to the engine in a small car.

Sophistication. From the computer systems that enable them to perform complex 3-dimensional movements – to the cutting edge of mechanical engineering excellence of which they represent – they are some of the most sophisticated, complicated and expensive machines humans have developed.

Accuracy. This machine is accurate to about 3 thousandths of a millimeter. A human hair is about 70 thousandths of a millimeter.

Capability. A CNC machine can make almost any shape. And they do – from the internals of a mechanical watch, the metal mold which is for the plastic objects which fill our world through to the crankshaft for a tugboat – a CNC machine made it.

Now let us get to the art bit. Early on in Bert’s exploration of his artistic pursuits, he noticed very little of the photorealistic art was made to be anything that could be described as (in any serious way) – conceptual. There was little beyond the display of the painter’s mastery of the depiction of the surface of things. There were a few exceptions, sometimes the idea, the conceptual value of the painting was there if you looked beyond the visual aspects. But it always took a back seat to the wonderful eye candy that is good photorealist art.

So Bert Ernie set about to create just that – a conceptual photorealist painting. A painting whose subject behind the artwork was more important than the art itself. The idea behind this work was to talk about the genre, the style that has come to be known as photorealism. The term photorealism was coined by Louis K. Meisel, but to Bert, any painting that looks close to what the human eye perceives; with a sharp focus and an accuracy of color and form – is photorealism. He believes that the first photorealist painters were the Seventeenth-century Dutch artists.

What Bert ernie learned in his discovery of how to paint in a photorealistic style was that the single most significant factor was – accuracy. Accuracy of color. Accuracy of form. Accuracy of position. The three A’s. That’s all there was too it. Bert literally discovered the idea of the three A’s from a book on art which had an explanation of the technique from one of the pioneers of the ‘new’ photorealist painters – Malcolm Morley. Bert put that simple idea, as best as he could, into his own development as a photorealist painter. With each small mistake made (and then corrected), each painting completed, Bert Ernie would refine the three A’s.

As Bert got better as a photorealistic painter, he also started to understand that the ‘art world’ had a tendency to either hate or just ignore the photorealist genre of art. Mostly it was seen as a nice visual trick. Critics would occasionally make a compliment to the artist’s skill but then proceed to add that there was not much to leave the viewer to think about. They were mostly right. Those photorealist artists who typically painted in the style of what might best be described as the ‘chrome motorcycle engine crowd’; were leaving the viewer with little more than a few minutes of eye candy.

As a way of making some kind of defense of the art form that Bert had come to love, he set about creating a painting that would speak of the qualities of photorealist art. So he created a painting, and then a series of paintings, which have as their main subject photorealism and its relationship to painting. This particular Deckel Maho Gildemeister painting wasn’t the first. Bert Ernie had painted another piece – Expensive tools before this. However, this artwork, the brochure piece, is the best at achieving its intended goal. It works on so many levels by using metaphors.

This brochure from a company that was then known as Deckel Maho Gildemeister (now DMG MORI) is an advertising piece which essentially brags about how good it is. How it is the best in class, the most powerful, the most accurate. It is the benchmark for all others. And this is pretty much true – this particular manufacturer is what might be best described as the ‘Rolls Royce’ of CNC machine tools. At the time Bert painted this – he believed that the genre of photorealism was the very best; the type most worthy of admiration by the art critics. Bert Ernie doesn’t feel that way anymore. And in the same way, he doesn’t think that by using that same metaphor to boast of his own skills as an artist (which was one of his aims then) is valid. There are just way too many photorealist painters who are extremely skilled for any one person to be described as ‘the best.’

Some of the other ideas Bert tried to get across by using a CNC machine as a metaphor for the photorealistic genre are still valid. He hoped that people could understand that the CNC machine is not only accurate but versatile; it can make just about any shape. A good photorealist painter can duplicate just about any photograph. They can copy a photograph of a person, a still life, or a landscape.

Bert also wanted to imply the power of the photograph. If the photorealist painter decided to copy a powerful image, then they would retain, perhaps even amplify, the source photograph’s power. Very few have done this. The one person who managed to do this was Denis Peterson, whose work of homeless people and slums is incredibly moving.

There is also one more metaphor Bert tried to use in this work. And that is how a great deal of new contemporary realism relies on photorealist painting techniques. He used a mostly unknown (to the average person) machine as a metaphor for the basis of all realist art. The ‘art world’ and critics rarely explain to the average person that much of the modern realist art that they celebrate owes a lot to the photorealist techniques which have been developed since the 1970s. The grid, the projector, the widespread use of photographs as a source; they don’t want you to know that the artists they champion all employ these things. The same things that they decry when it comes to discussing an artist whose focus is mostly on their skill, on technique, on accuracy. It is a bit like how at the start of this little essay he has to explain the incredibly important machine to our modern world. The machine that the average person doesn’t know about. The machine that is the basis of everything else that follows.

If you would like to see the product page for the latest version of this machine then please check out the link here.

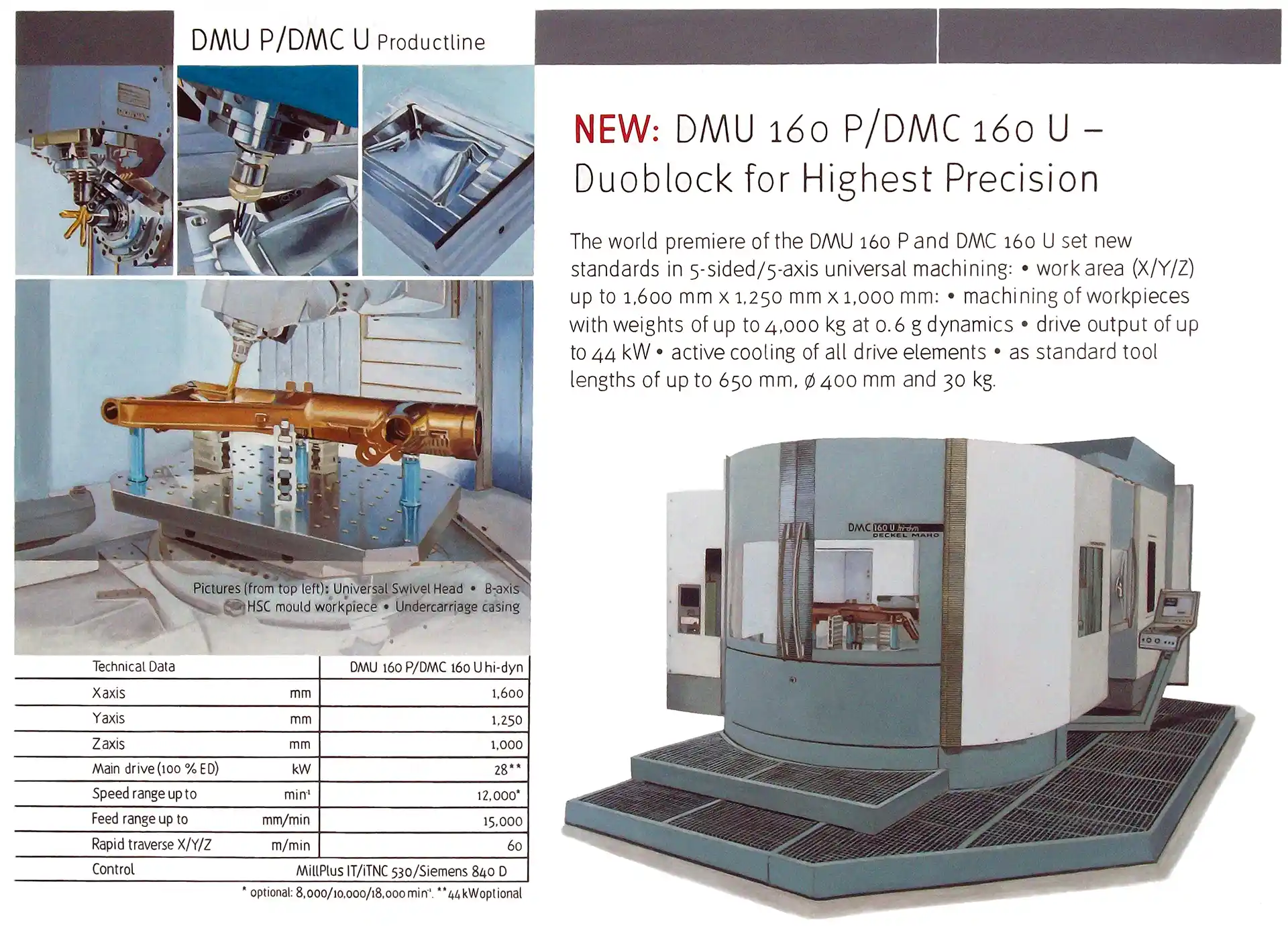

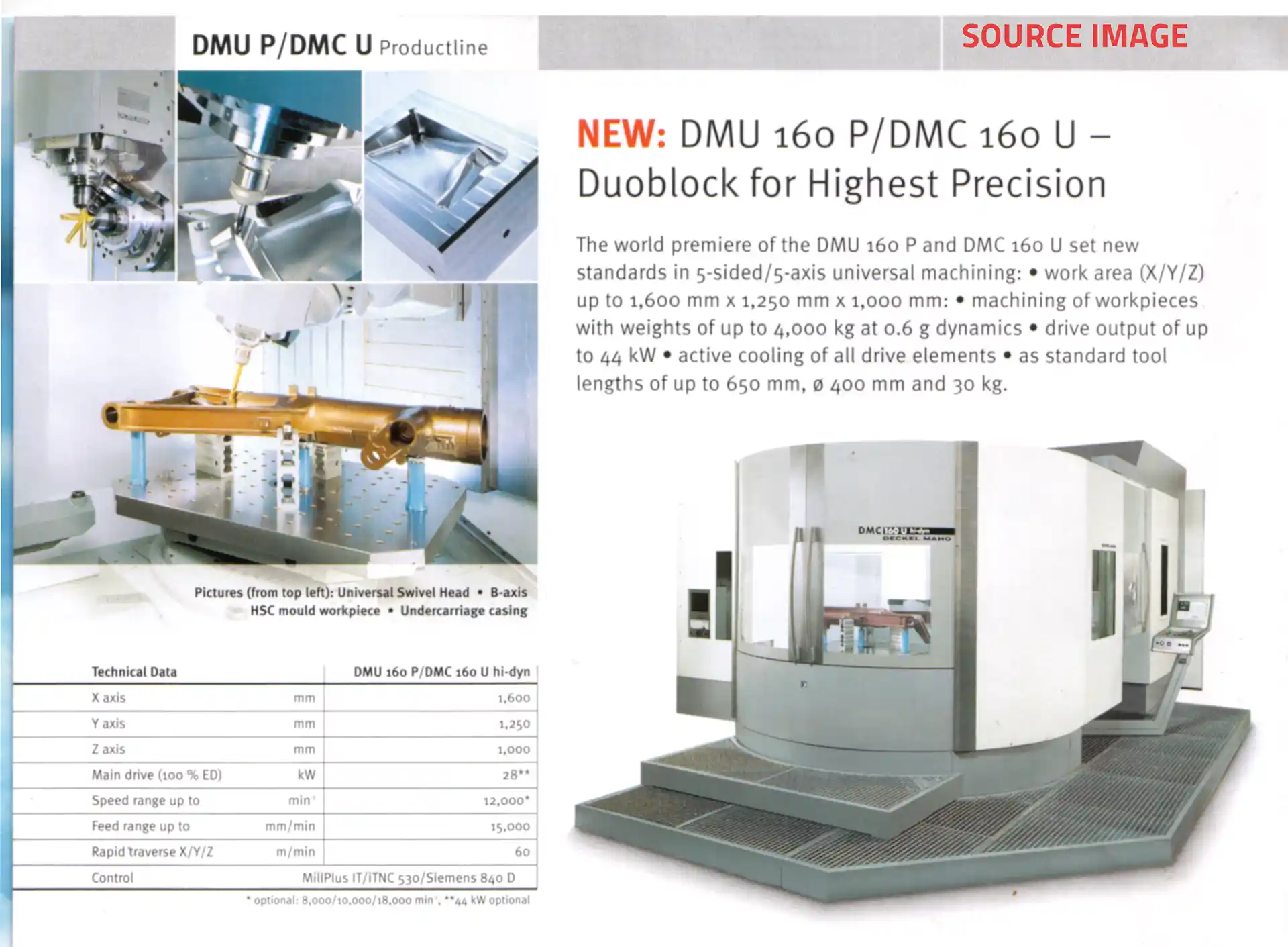

Source image of realism painting Deckel Maho Gildemeister

Detail views of realism painting Deckel Maho Gildemeister